ARGOMENTI DI ARCHITETTURA ISSN 1591-3171 N. 11/2019

DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.16417.15209

ABETI Maurizio (IT)

Maurizio Abeti

Professor of the Course in History of Contemporary Art and Applied Arts

Universitas Mercatorum / Degree Course: L4 – Product of design and fashion

Piazza Mattei, 10 – 00186 Rome (Italy)

Tel. +39 06.883733300

email: maurizio.abeti@unimercatorum.it

Abstract

The story of urban green in the center of our cities has lasted, between birth and decline, about a century in all. It was, therefore, one of the most ephemeral and probably even more expensive urban events; and where it is not suffocated by illegal car parks, cloisters, and petrol stations, by electric cabins, it is still one of the wonders of a city.

In the past, it has been considered a priority value and has attracted great interest at the local level, both in large and small towns.

There is in the architects, and even today in the philosophers, the idea that history can be immediately exploited helping to solve problems that can not be adequately addressed, in terms of design. Nowadays history presents a repertoire of alternatives and possibilities but in many cases, it teaches that this aim is very difficult to achieve, anyway if well planned it has an extraordinary function.

1. Introduction

Cities are developed by a need for interaction: they are structured around nuclei where there are advantages for all professional activities, for purchases, for leisure, for the life that takes place around them. This search for centrality causes a high density of population, so it becomes difficult to create, within the urban fabric, those oases of green essential for the quality of life.

The problem of the balance between green spaces and high density was born with urbanism. In ancient cities, which rarely exceeded 20-30,000 inhabitants, they moved on foot, which reduced the radius of the built-up areas. If then fortifications were necessary, the built perimeter had to be kept to a minimum, and the density was so high that it became difficult to create gardens, walks or parks. For a century, the transport revolution has encouraged the expansion of cities; but even if today’s big cities are home to 10 million people, space is still very much in the center, and the area where prices are prohibitive and uncontrollable has become much larger.

If we want to redevelop the urban fabric and improve the quality of life for everyone, we need to take a look at the vitality of green spaces, gardens and urban parks. The problem today consists in the possibility of providing a sufficient amount of green for each inhabitant, as well as in the choice of the forms that best contribute to making the built environment fit for human beings.

2. A look at the past: from the medieval “garden” to the palace park

The medieval cities are “dense”; despite the dangers created by the overcrowding of the inhabitants, by fires and epidemics, the interest in participating in exchange activities is predominant. The houses are contiguous, the streets “narrow”, the squares too small to accommodate many trees. Gardens exist, but they are quite rare within the urban core. When urbanization develops on a rural plot, lots are often narrow and long and the end is occupied by gardens. With the increase in density we end up building on them; in fact, the buildings are built around a series of courtyards. The Church has fewer problems than individuals to create gardens, but the cloisters have only small spaces. Convents, on the other hand, are often better organized, as they produce a part of their seasonal fruit and vegetables on their own.

The garden is, first and foremost, a productive space: it contributes to the supply of citizens by supplying fruit and vegetables and sometimes even wine. Despite being an indispensable element, it cannot be inserted in the heart of the city, especially when it is fortified, and therefore occupies a privileged place in the suburbs or on the outskirt. During the XIII and the beginning of the XIV century, when the maximum increase of the population is registered, in many cities new walls are built, but they are then too large to be actually filled. These walls, therefore, enclose a strip of gardens inside, so that later urban expansion can resume without further modifications: the lots are ready and the roads exist, even if they are narrow.

In urban life, the garden is not taken in consideration for recreational life. It belongs to the aristocracy: it exists in castles, surrounded by walls, within which the noblewomen can play musical instruments, work or play immersed nature “on a human scale”, under a flowered portico, in the shade of a veranda or of a pergola. At the same time in the city, there are few families who own a garden attached to the house. Most of the palaces, at the end of the Middle Ages, in Italy as in France, open onto a narrow courtyard. Only the very rich princes or merchants can afford a garden in the city. The park, as a place of privileged rest, has not been born yet.

Renaissance changes habits. Instead of building vast gardens within the city, patrician families buy the lands nearby and are able to make a profitable operation, rationalizing the use of land and intensifying production, as evidenced by the mid-fourteenth century, the study of the fresco of “Buon Governo” by Ambrogio Lorenzetti. But suburban land also offers a cool place to spend warm months. From the still feudal manor built at the beginning of the fourteenth century, we move to the villa. The letter in which Pliny describes his own rural house, Laurentina, makes humanists dream: they imagine a new art of living and a frame that suits it: we rediscover the “otium” of the ancients. During the fifteenth century, in Florence, they learn to make these suburban residences more enjoyable: in Cafaggiolo, Bartolomeo Michelozzi, called Michelozzo, animates the facade of the Medici villa with windows and surrounds it with a garden.

The main innovation comes from Giuliano da Sangallo, to whom Lorenzo il Magnifico entrusts the construction of the villa at Poggio in Caiano, at the beginning of the 80s. The gardens of these new villas are populated with statues: the humanist Poggio, in fact, installs his collection at the villa Valderania and Pope Paul II takes this idea to Rome, at the Palazzo Venezia, Giulio II transforms a courtyard in the garden of the muses at the Belvedere. The “Sogno di Polifilo” of the Colonna transforms the garden into the frame within which the mythological fable unfolds, and the same thing suggests the “Arcadia” of Sannazzaro. In the course of a few decades, the garden is transformed; aristocratic life is no longer conceivable outside this incomparable frame.

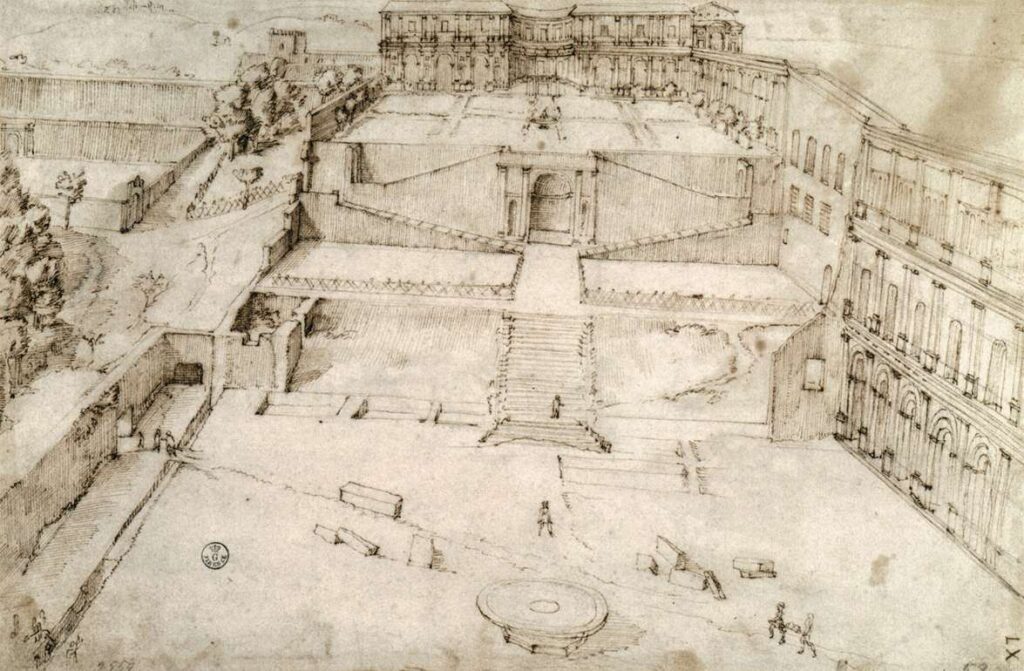

The garden spreads more and more on the edge of the city and is structured with even greater wisdom. Bramante transforms the Belvedere1 into the first great open-air architecture; the art of creating

games of stairways, terraces, exedras, of diversifying the space of the garden, embellishing it with perspectives and animating it with fountains, waterfalls and pools of water developed throughout the century.

Rome is transformed by this evolution. To the large villas in the countryside, in Tivoli, in Caprarola, in Bagnaia, are added the buildings that surround the medieval city, creeping in the middle of the ancient ruins, or enhancing the surrounding hills: Belvedere, Villa Madama, Villa Medici, La Famesina, the gardens of the Quirinale or those of Villa Montalto.

The new art of gardens transforms the green space into a domestic space, into an inhabited space: for the society, it becomes a place dedicated to parties more than to everyday life. It learns to live its refined existence within a natural frame: it is an exceptional lesson for those who are interested in the quality of life.

3. Gardens and parks in the classic Baroque city: nature as geometry and harmony

The cities of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries still do not have green spaces for the citizens, but nevertheless there is a change in the way of developing the structure of parks and gardens.

The Renaissance suburban garden was reserved for a small cultured and lucky elite: few were the families able to buy those 5, 10, 20 hectares, or even more, of splendid urban realizations. In Paris, only the royal family could afford it and the queens are those who impose a Florentine or Roman model. Caterina de ‘Medici had the Palazzo delle Tuileries built-in 1563 and commissioned the first large French garden built on the edge of a city. She

indicates to her architects the model of Palazzo Pitti: it is a matter of merging the garden and the building into the same whole. Maria de ‘Medici repeats the experiment and promotes, starting from 1615, the realization of the Luxembourg Gardens. These parks are opened almost immediately to the public, albeit to a limited public: access to the poor and beggars is forbidden. They offer the opportunity to escape the crowds and the gloom of the streets but have nevertheless been designed for princes and their guests.

The example of the royal family is soon followed by the whole wealthy class: the city palace is transformed and becomes conceivable only between a courtyard and a garden. The latter does not have the size of the large parks of the wealthiest, but whether it measures 50 are, or one hectare or two, it offers the family a space in which to play, live, or receive guests.

The Marais, the districts of Richelieu and Saint-Germain, are thus filled with luxury homes. Urbanization spreads but does not cover the entire city area: the urban fabric is dotted with vast green areas, although nothing is visible from the streets.

The same tendency is followed by the Church, after the Counter-Reformation. The religious orders of urban vocation, the Franciscans, the Dominicans, the Augustinians, are prone to preaching and use the gardens only for the production of a small amount of fruit and vegetables. But now the cities are hosting ever-increasing congregations, which are dedicated to the education and care of the sick and that, unlike the past, are predominantly female.

Therefore, the production of vegetables for all, the walks for the nuns, the recreational spaces for children and adolescents, are necessary. The surfaces do not have the extension of those of the great medieval convents of the Benedictines but are more intimately integrated into the urban fabric.

The citizens, in the Mediterranean countries, have always been dedicated to the “walk”, the “promenade”, or the “paseo”: the public promenade is the core of social life in these regions. During the sixteenth century, the atmosphere created by the life of the court, the habits of the Italian aristocracy change: carriages are used to go out for a walk, even the noblewomen can access to a pastime reserved to men. The idea was born in France at the beginning of the seventeenth century: Sully had the Mail de l’Arsenal (today’s Boulevard Morland) set up in Paris in 1599, and later Maria de ‘Medici, decided to create, in Cours-la-Reine, the correspondent of the Florentine walk of the Cascine, along the Arno.

The success of the “promenades” is prodigious in all the capitals. When the destruction of the city walls, which have now become useless, gives rise to free spaces, the habit of creating tree-lined avenues like the Cours-a-Reine is born, and of giving them an unusually wide width. Thanks to the “boulevards” that are beginning to appear, the population has access to the wooded areas, especially in Paris, where Louis XIV gives the first example. Later, in the new neighborhoods, the avenues resume the same model. The avenue, however, slightly trivializes the frame of the walk: in fact, it does not yet have the width that distinguishes the places where the urban show takes place. So, more detailed “promenades” are often planned. In Montpellier, the Peyron, built for the walk rather than the parade of carriages, foretells, in some ways, the public gardens of the future.

The “promenades” are almost always located on the outskirts of the city, in place of the ancient fortified walls or in newly built areas. The impact is therefore reduced: they are only accessible to a part of the population and are too far from high-density areas to attract a large crowd. To make sure that the “promenades” become the central axis in the built-up space, a transformation that begins in the eighteenth century is necessary, when new forms of tourism are established. In Bath, a fashionable resort in Georgian England, one of the most beautiful “promenades” of the era is built on the right bank of the Avon: the habit of getting there on foot, on horseback or in the carriage, to make an appointment or to show off with elegance is spreading. The tourist city now lives in the name of a double centrality: that of trade and services, often linked to the pre-tourist nucleus, when this exists, and that of the “walk” where local public life takes place. The Bath model quickly asserts itself. In France, d’ Etigny traces the avenues that bear his name in Luchon during the 1950s. Even by the sea, the promenade manages to prevail, first in England in the late eighteenth century, in Brighton, and a little later on the continent, for example in Nice, where in memory of its creators is known as the Promenade des Anglais.

he large parks of princely families, the urban gardens of the aristocracy, the convents’ gardens, the “walks”, here are the places where the green occupies a place of honor within the classical or baroque cities. Most of these parks, moreover, are not open to the public and have not been designed for it. The only places open to all are the stands of the “a redans” squares, very widespread in the military architecture of the time: here is the possibility of wonderful outings for children and citizens, even if their location, as well as the regulations military, limit the frequency. The classical and baroque age never directly addresses the problem of green spaces and the possibility of allowing access to all. It imagines various types of structure to meet different needs: green is, in some way, intimately integrated with everyday life, it is never a foreign body within urban space.

4 The landscape park: nature on stage

In the seventeenth century, the ambition of the creators of parks and their users is enormous: they aspire to express an ideal of harmony and measure, to create a perfect environment and to represent, through flowerbeds and pools, a specific conception of the cosmos. Louis XIV orders the construction of Versailles to make his power shine, but the park, despite its triumphant geometry, is first and foremost designed to preserve the pantheon from every Arcadian dream. Even though the whole thing is made with millimeter precision it does not disturb the rationalism of the “Grand Siècle”.

The eighteenth-century will have another sensitivity, but the creators of English or Chinese landscape gardens have a concept of their mission as high as that of their predecessors: they aim to stage nature, to make it even more “natural” and seductive than spontaneously it can be. The park is no longer designed by the analytical gaze of a surveyor who places himself at the center; its curves, its sinuosity, its typical features have the task of making people pay attention, favoring a pause, arousing the dream. He who walks there is no longer accompanied only by a multitude of muses, nymphs, fauns and gods. The meadows, the trees and the groves push him to meditate on the Creator; nature is the great teacher of thought of this century, characterized by deism. The parks thus become a pretext for almost metaphysical experiences, as underlined by the inscriptions that the Marquis de Girardin disseminates in Ermenonville.

The French gardens show off to testify the power of those who design them, to give those who discover deeper perspectives, the vertigo of the infinite. The parks are perhaps even more extensive, so much so that it seems necessary to shape the ground to reconstruct nature in all its aspects and in all stages of its evolution (the pavilions scattered randomly make one think of humanity with ephemeral triumph, followed by long declines reminded by the ruins).

The ambitions increase as the image of the nature that is created becomes more complex. When William Kent, one of the great protagonists of the landscaped garden, begins the transformation of the old parks to the French ones, which the English aristocracy had made to plan at the end of the last century, the idea of spontaneity of nature is not yet well defined: Claude Lorrain’s paintings are imitated much more than wild nature; the inspiration of “Capability” Brown, Britain’s most famous landscape gardener, is even more serene.

5. The realization of the concept of public green

The art of parks has therefore become, in the eighteenth century, less and less urban: how to create, in fact, the illusion of the countryside or nature on a strip of land? Pope makes this attempt in his Twickenham garden in a sense, he will be the first to have created a landscape garden but how to feel lost in nature when you have only two hectares of land around? It is therefore affirmed an art of the distinctly urban garden: the bourgeoisie, who until recently had only a vegetable garden, have in front of the entrance, a flowered space and shelter in the shade. The need for natural space is felt at all levels. How can it be satisfied? Only traders, officials or landowners can afford the five or ten are to carry out a coherent project.

In England, the passion for nature is more widespread than on other countries of the continent. In Bath, where fashion makes the English aristocracy roll in during summer, would be impossible to offer a garden for everyone. John Wood finds a solution: in the “squares” which are

projected on the image of Parisian royal squares and European capitals, he does not put a paving pavement at the center, but a garden. The “square” allows each of the houses that surround it to have a small private garden; beyond it there is room for a larger garden, which is co-owned by all those who overlook it. They are not public gardens yet, but the idea is elaborated. The solution of John Wood is taken up in the “squares” that still nowadays make up the glamour of the London district of Bloomsbury. When the layout of Regent’s Park was decided, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the formula “private property at the edges and co-ownership in the center” is still used. It will be only after the failure of the company that operated the subdivision, that the park will finally be open to the public.

In many European public gardens there are traces of this phase: the houses that flank the park have private gardens that make the central space extend beyond the gates: this is the best way to have your own space and take advantage of the opening of the public space.

The city’s administrative authorities increasingly feel the need to open green areas to everyone: because there are sometimes military requirements. In Switzerland, for example, the parade ground and the military training area are progressively planted with lime trees, elms, chestnut trees, and the lawns are looked after: they continue to be used for military training, but allow everyone to go for a walk. Towards the middle of the eighteenth century, it is mentioned that parks and gardens are designed to be open to the public: in France, for example, the Fountain Gardens in Nimes dates back to 1743.

The study of medicine progresses. The awareness of the deplorable hygienic conditions of most urban housing is felt more. Epidemics are easily attributed to the miasma and other putrid emanations that cannot be avoided in the old and too populated neighborhoods: there is no means for rehabilitating the urban fabric. It would be necessary to destroy everything and rebuild with wider roads, with better paving, with sewers for the evacuation of waste water. The wide avenues, open to the air, seem to be the ideal way to rehabilitate the neighborhoods, but, since they cannot be realized, it is appropriate to offer spaces where families can breathe, children play, and where everyone’s health can benefit. The tendency to create public gardens, had a rapid affirmation since the eighties, is so linked to the new concept of medicine of which Paul-Michel Foucault – French philosopher, historian of ideas and social advocate – was the historian.

In France and in the countries where the revolutionary armies and later the imperial ones, brought new institutions, the transformation of urban fabrics is facilitated by the nationalization of the clergy’s assets: the public administrations take possession of the bishops’ parks and the green areas of the great convents to open them to the public. In France, even the goods of the emigrants are added to those of the clergy and this means that the public administration has an even greater number of green spaces. The ease with which illuminated towns open such extensive areas to the public is extreme. In Paris, the entrance until then reserved, both at the Tuileries and the Luxembourg Gardens, becomes free. Cities like Rennes have magnificent complexes of the Gardens of Palestine, to mention one and other examples would be many to be cited.

Napoleon is not indifferent to the gardens and the empress Giuseppina supports him. The castle of La Malmaison, in Rueil, his favorite residence, is

soon surrounded by a park similar to the great achievements of the late eighteenth century, of about 800 hectares. Its arrangement follows the English style, then dominant, but it becomes above all a field of acclimatization experiments. Aimé Bonpland, the botanist who had followed Alexander von Humboldt (German naturalist, explorer and botanist) in his South American circumnavigation, is a master in this work: he makes the most varied species come from all over Europe and Giuseppina gets from his imperial spouse the licenses that allow her, to import, in full continental block, plants that English nurserymen and collectors will later acclimatize.

It is in Rome that Napoleonic action obtains the greatest successes. As soon as the city is annexed, the prefect de Tournon proposes an ambitious project. Of it, only the park to the north, the park of the Great Caesar, at Pincio, is finally realized by Giuseppe Valadier, an Italian architect, urbanist and archaeologist, an important exponent of neoclassicism in Italy: for that period, it is still a rare example of a large urban park designed for public use.

6 The era of the public garden

The eighteenth-century is the great era of the public garden. All cities are equipped with urban parks, forests designed in the suburbs and neighborhood gardens that offer play areas for children. The work of Baron Haussmann, who was a prefect of the Seine Department of France chosen by Emperor Napoleon III to realize an impressive program of urban renewal of new avenues, parks and public works in Paris, is exemplary in this sense.

Carlo Luigi Napoleone Bonaparte, better known by the name of Napoleon III. spent most of his exile in England and kept a nostalgic memory of Hyde Park and Regent’s Park. These are “palace” parks, reworked in the 18th century according to the landscape style. And this is what Napoleon dreamed of for Paris. He wanted to surround the capital of woods and parks, but he contented himself with the modest settlement, to the east and west of the city, of the Bois de Boulogne and the Bois de Vincennes. In the urban fabric of Paris, there is the Montceau park, the Chaumont hills park, the Montsouris park, as well as “squares” and smaller gardens. The practical realization of this project is entrusted to Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand, a French engineer, the composition is defined with taste, everything is designed to harmonize the whole and to last: the borders of the “parterres”, the benches, the bridges. The English model is evident, asymmetry reigns in the design of the groves, the avenues are meandering, the water sources irregular. The lakes greatly appeal to the public: on sunny days it is possible to hire a boat for a boating trip.

But not everything follows the English model. Grassy meadows are not open to the public and leave a wide margin, along the buildings or on some stretches of the banks of the lakes, to the flower beds. This is how a French tradition developed from 18th century texts, a period in which the flower beds begin to illuminate, with their bright colors, the French gardens.

In the 19th century, Germany had a great diffusion of public parks, perhaps the most remarkable compared to any other European country. The first realization, in 1824, is that of a large park in Magdeburg. Almost immediately they follow Berlin and, in turn, the other cities. In Vienna the destruction of the old city walls on the ramparts allows the city to be remodeled: it is surrounded by large public buildings, but also offers magnificent walks and gardens.

Frederick Law Olmsted, the charismatic landscape architect of Newburgh, New York, creates the most famous parks in the United States: Central Park in New York, Prospect Park in Brooklyn and, even if he does not have the

task to realize the proposed projects, he takes part in the choices for the parks of Chicago and San Francisco. For his creations, Olmsted draws great inspiration from what is done in Europe, in Paris, and in particular in Vienna. But he designs parks for a society that affirms opulence. For the wealthy New York bourgeoisie, the visit to Central Park takes place in the buggy and the love for speed is already a pleasure for many. Therefore, it is advisable to ensure that the avenues do not stop abruptly. Olmsted imagines elevated intersections with connections to enter and exit the avenues without danger: it is already the technique of the four-leaf clover intersecting the highways. Nothing to object to if these are first defined as “parkways”: it seems impossible to separate them from the environment of the woods and meadows for which these complex joints were originally imagined.

The ambition of landscape architects soon increases in the United States. After Frederick Law Olmsted, American landscape architect, the idea that a city should be equipped with parks that form a system gains popularity. It is therefore thought to create a green lung for urban centers along which parkways facilitate general circulation. Boston offers the first example of a complex coordinated realization, but the Middle West, where urbanization reached its decisive phase in the last three decades of the nineteenth century, offers a determining experimental terrain: Kansas City, Minneapolis, Cincinnati and, to a lesser extent, Chicago, realize parks connected by long green corridors. Urban space comes to be interrupted in this way by wooded flows that bring gardens close to all the neighborhoods. We are not far from the hierarchical conception of Alphand for Paris, but here interventions are inter-related.

7 Towards a much closer union between city and nature: the model of the garden city

The movement for the creation of urban parks thus brings the nature and the city together more intimately: Chicago is baptizing “urbs in horto”, the garden city: and it is to this that efforts are made to integrate the green into the urban fabric.

The landscape park does not contain, at the origin, any building and, in this, it differs from the Chinese garden, which instead is designed to be viewed from pavilions or walk under covered avenues. Only false ruins or a few gazebos recall the work of men. The fashion of the picturesque brings a change: the enthusiasm for nature spreads, there is passion for the rustic farms with sloping roofs: the pavilions of the queen, in Versailles, are still a testimony.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, we are looking for a formula that can closely link the town to the garden. The models of villa that reign at the time do not adapt, unfortunately, to realize this union: they remain linked to the memory of Laurentina, of which Plinio exalted the charm in his letters. What did this villa look like? Certainly, to those that Palladio built in Brenta valley, between Padua and Venice, or around Vicenza. Their architectural masses, distribution, perfect symmetry recall vast spaces. They are not made to the size of bourgeois families. The architecture manuals published around 1800, like that of Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, an important figure in Neoclassicism, propose designs and terraces of classical or Tuscan inspiration, but appear a little too reductive to be attractive.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, therefore, experiments are multiplied and we try to design houses suitable for families of average size, with a garden of 1000 or 2000 square meters. Some experiment with the exotic model: the first villas were often in shape of bungalows, surrounded by galleries, as often are found in the tropics: and in fact, this is not the model that has become usual in the French Antilles or Louisiana? And is not this the model adopted after Brighton, in the new English seaside resorts and also in Quebec, where it will end up being considered the only true French model? In France itself, at the time of the Restoration, places like Arcachon are filled with bungalows.

However, the success of this type of architecture remains limited: perhaps it seems too fragile for French or English taste. Ultimately, the solution is found in a rustic key. It can already be seen in the hamlet Boileau in Auteuil, the Oise department of the Upper France region, built during the July Monarchy. But the tendency will be clarified above all during the Second Empire. On the outskirts of Paris, Palluau, a banker, performs an experiment successfully: in Vésinet he installs a whole community in a park, in which he distinguishes public green and private gardens, preventing the delimitation between the two from harming the harmony of togetherness. The seaside resorts offer similar opportunities: the winter city in Arcachon, in particular.

It is therefore in France that, in the 1960s, we are closer to finding a satisfactory formula for garden cities. However, the tendency is slow to assert itself. Railway companies are struggling to realize the profits they could make by multiplying their daily trips. It is only around 1890 or 1900 that suburban expansion begins to take on a real physiognomy.

In England the idea of the garden city is systematized first; it is the core of the action of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, a British politician and colonization theorist in Australia and New Zealand, in the 1930s. The cities he makes found, or those inspired by his ideas, combine all parks and built-up areas, and are often surrounded by a wooded belt and prairies, such as Wellington, Dunedin and Adelaide, as well as numerous towns in southern Australia. Other cities are built around the perimeter of a park, designed according to their size (e.g. Christchurch), or are flanked by gardens at the four corners of a previously traced space, such as Melbourne. Are they real garden cities? No, in reality it is more a juxtaposition of built spaces and natural spaces than an integration.

When we start again to study the garden-cities, at the end of the century, we want to find more radical solutions: it is in a real park, in the middle of the trees, that the houses must immerse themselves. Ebenezer Howard2 combines in his projects what remains of Wakefield’s ideals and what he has learned about “urbs in horto” during his long American stay. The impact of the movement created by him far exceeds the limits of the new cities: all the suburbs are affected by innovation, especially in the Anglo-Saxon countries.

8 The reappearance of private greenery and the crisis of reference aesthetic models

The creation of urban parks and gardens systems took place in the nineteenth century in a curious atmosphere: the landscape gardens that are drawn no longer respond to any live current of inspiration. In this field, as well as in others, people tend to be attracted by easiness and eclecticism, even if the latter has less material to be used than in the architectural field. In fact, it is possible to play only on a reduced range of elements: there are no structural ones, such as terraces and Italian staircases, great perspectives on the French side and soft English lines. The models of the arid countries, those of southern Spain or of the Muslim countries are difficult to transpose in cool and humid climates. Japanese gardens began to become familiar only during the 1980s. Cities are thus adorned with realizations that are not motivated by any authentic aesthetic aspiration. The return to classical forms, begun in France by the Duchées and under the influence of the Andalusian garden, so marked in Jean Claude Nicolas Forestier, French landscape designer, is not enough to renew the old formulas of a century: there is, among the creations of the 40s and 50s and those of the interwar period, an evident continuity. However, the context has changed a lot, which explains the discredit in which the traditional urban park falls.

The art of gardens is subtly transformed by the new passion for flowers: the bushes are colored and composed with greater skill. From this, however, it is not possible to deduce new principles of composition: the tonal garden is born. This could only come from an impressionistic sensitivity, and that is what W. Robinson finds during the years he spent in Paris as a reporter. He loves the joy that the flowers give to the French gardens, but detests the formal framework in which they are inserted. Looking at the flowering expanses of a thousand species, he discovers the model that, throughout his life, will try to make triumph. The garden is, for him, a colorful composition that the art of the gardener allows to continually renew, following the rhythm of the seasons and the blooms. At the same time Claude Monet moved to Giverny, a village in the Normandy region in the north of France: it is in this small space, less than two hectares, that he creates something to which his painting will be inspired for years. However, it is not from Giverny that the fashion of the tonal garden spreads, but from England: Gertrude Jekyll, British horticulturist, designer of gardens, an artist who, due to his poor eyesight, was forced to give up painting, he found in gardening the way to satisfy his passion for colors and translate the principles of W. Robinson into practice. Joining E. Lutyens, one of the most gifted architects of his generation, Jekyll imposed his compositions in England, throughout Europe and the United States, creating more than 400 gardens.

The new tonal garden can enliven remarkable parks, such as Varangeville, a municipality in the department of Meurthe-et-Moselle, in north-eastern France, near Dieppe. But the maintenance of this type of gardens requires

incessant care: it is easier that these can be lent to the small plots that surround the “cottages”, whose gardens had inspired Robinson and Jekyll, than most of the parks. The renewal of the art of gardening is almost always too expensive for municipal budgets and the floral compositions are too fragile to bear the presence of anarchists. It is therefore rather in the private garden that this renewal will take place.

The idea of the garden-city, and its interpretation in most of the suburbs, is based on this consideration: it is useless to create public green spaces at high costs if everyone has, around him, a land on which to exercise his activities, to prove his creative genius, or get some rest. Almost everywhere, the drive to create large public gardens decreases during the first half of the century: in this period, in Paris, there is nothing left that resembles the daring creations of the Haussmann period. And neither in London nor in Rome, nothing better is accomplished. In the United States, the balance is more positive thanks to the “parkways”, but they are actually just lanes for moving on and not spaces in which to live. Only in Spain great works are realized, for example in Barcelona, where Forestier designs the garden of Montjuïc for the International Exhibition of 1929.

The consecrated style of the urban park no longer corresponds to the new aesthetic aspirations. Moreover, little can be done for the lifestyle of modern life: in the nineteenth century, in continental Europe public gardens were frequented, in a compassionate atmosphere: the needs of a society that spent its free time dressed up for partying were met, rather than dressed in sporty clothes or suitable for staying in open air. In England and the United States, the situation was somewhat different, and because the large grassy expanses of the Lancelot Brown parks, more commonly known as the “Capability” Brown, English landscape architect, resisted almost all the treatments, the free time was occupied more actively: the idea of “formal” park tended to scare more than to attract.

The garden is made for play and for walks. The private one allows to perform a minimum of exercise: the maintenance of flower beds and of lawns is often the only physical activity of the middle classes. The less well-off urban populations are still living in high-density spaces in this third millennium: the private garden for all is not really possible.

The transformation of the lifestyle implies simultaneously a profound transformation of the garden: the differentiation of its appearance, as well as the stagnation or regression of its public form. At the same time, the analysis that is made of urban balance also changes.

9 Conclusion

The triumph of the quantitative approach: a conclusive balance

Throughout the nineteenth and in almost twenty years of the twentieth century, we are convinced that gardens and / or parks are useful for health, but hygienist arguments are at the beginning. History teaches us that with the discoveries of Louis Pasteur, founder of modern microbiology, we become aware of the level of urban mortality.

Today, the damage caused by smog is now well documented. Breathing fine dust promotes the onset of cardiovascular disease, asthma in healthy subjects and facilitates the formation of respiratory allergies, and causes mortality due to natural causes, including cancer.

Only direct sunlight eliminates it, so health depends on good sunlight. Nature is reclaimed in the city for new reasons: it no longer serves only as a frame for games or walks, but must penetrate everywhere and creep in, with large lawns, between buildings, so that the sun can continuously eliminate harmful germs.

Nature acts with its own mass and through the way which it integrates itself with the built, rather than through its structure or organization. It is understood that the green masses allow, thanks to the action of chlorophyll, the air to re-oxygenate. Does carbon exchange in carbon dioxide necessarily take place in the urban area? This question does not yet arise: the predominant idea is that a certain area of grass or woods is essential to its biological balance. It is precisely this vision of nature as a mass phenomenon that corresponds to the appearance of the expression “green spaces”. The city-nature relationship is now included in the quantity register.

Does this mean that there is an increasingly undifferentiated use of green spaces? No, far from it: as free time grows and the ways of using it increase, the environment in which it is possible to spend it becomes larger. People are no longer content with a quiet walk with the family on Sunday afternoons. There are now activities suitable for every age, sex and temperament. To practice them, tennis courts, golf courses, soccer fields, basketball courts, rugby courts etc. are necessary. All these spaces have the same purifying function as cleaning the air and the elimination of microbes, which justifies their use in general terms, but urbanists risk to forget the variety needed for the layout of the territory. Once the “standard” initially set at 10, 20 or 50 square meters of green for each citizen is reached, there is a tendency to believe that the territorial structure is completed.

But the green spaces do not all participate indiscriminately in the well-being of citizens. Unfortunately, functionalist urbanism has forgotten it. Reading Le Corbusier, listening to those who remain faithful to his teachings today, one gets the impression that nature is consumed by citizens only through the eyes; it is enough to live in a building which overlooks on a lawn, on the bush or on woods to escape urban stress: a healthy city is a city where you can see the green from every window, even if only from a distance without the possibility to use them.

The poverty of this analysis translates into defective accommodations. The new quarters are ventilated, but in the “meadows” that separate the buildings there is a much denser atmosphere, as with the intertwined circulation there is still a high level of acoustic and atmospheric pollution. The areas are uncomfortable and do not offer sufficient support points for leisure activities. The green spaces are present everywhere, but the use that can be done is not personalized. Security, in the absence of organized surveillance, is badly secured. The gangs of teenagers are the only ones to have space in such an undifferentiated environment, and shrouded in terror. The large woods, which quickly make the amount of green spaces rise in the statistics, are often a negative element because they are badly frequented and therefore unsafe.

The contemporary growth of the cities has been accompanied, thanks to the car, to an expansion that favors the close relationship of the spaces built with the green spaces. However, due to the lack of in-depth reflection, the set-ups have proved unsatisfactory. Without forgetting that for cities free from smog and increasingly smart, participatory and inclusive urban centers, they also need actions of urban regeneration and redevelopment, energy efficiency interventions and more green spaces, understanding that only the expansion, which once seemed indispensable, it no longer has the same advantages. Certainly, it is not necessary to appeal to the rain dance to hope that the levels of fine dust will lower and thus avoid the smog emergency. We need an enlightened urban policy so that the quality of life really improves. We must start again to conceive less generic urban assets, reuse parks and gardens of the past and imagine new ones in which there is the possibility of carrying out other types of activities.

Bibliographic notes:

1. James Ackerman, “The Belvedere as a Classical Villa” (Vatican City: Vatican Apostolic Library). Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 1951 pp. 70-71. doi: 10.2307 / 750353. Excerpted on 24-01-2014.

2. Ebenezer Howard, English urban planner, in his essay A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898), which was one of the most important texts of the late nineteenth century, on the theorization of utopian cities, describes the idea of Garden City or garden-city as the ideal city on a human scale, which indicated areas completely immersed in the green.

Bibliography

– Charles Eliot Beveridge, Paul Rocheleau, Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing the American Landscape, New York, New York: the publication of the 1998 universe.

– Massimo De Vico Fallani, History of the gardens of Rome in the 19th century, Newton Compton Editori, Rome1992.

– Adriana Ghersi, Anna Sessarego, Proceedings of the Seminar “System of the Green Urban Ecosystem”, Alinea Editrice, Genoa 1995.

– Marie-Luise Gothein, History of the art of gardens, vol. I, Olschki Editore, Florence 2006.

– Benedetto Gravagnuolo, Historia of urbanism in Europe 1750-1960, Editori Akal. Madrid 1998.

– Pierre Grimal, The art of gardens. A brief history, Rome, Donzelli Editore, Rome 2000.

– John Dixon Hunt, William Kent, designer of landscaped gardens: an evaluation and a catalog ofhis projects, Zwemmer, London 1987.

– Lucia Milone, Urban Green. Between nature, art, history, technology and architecture, Liguori Editore, Naples 2003.

– Riccardo Pollo, Designing the urban environment. Reflections Tools, Carocci Editore, Rome 2015.

– Virgilio Vercelloni, Historical atlas of the idea of the European Garden, Jaca Book Editore, Milan, 1990.

– Little, Charles E., Greenways for America (1990), Johns Hopkins University Press.

– Fabos, Julius Gy., Ahern Jack (Eds.) (1995) Greenways: The Beginning of an International Movement, Elsevier Press.

– Lohrberg Frank, Urban agriculture in urban and open space planning,Faculty of Architecture andUrban Planning at the University of Stuttgart, 2001.

– Bradley C., Millward A., Successful Green Space – Do We Know It When We See It, Landsc, Res., 1986. Ulrich, R.S., A esthetic and affective response to natural environment, Behav. Nat. Environ. 1983.

– Karmanov, D., Hamel R., Assessing the restorative potential of contemporary urban environment(s): Beyond the nature versus urban dichotomy, Landsc, Urban Plan, 2008.

– Turner Tom, Garden history: Philosophy and design 2000 BC–2000 AD,

Routledge, 2005.

– Carroll Maureen, Earthly Paradises: Ancient Gardens in History and Archaeology, London: British Museum Press, 1986.